Property Guardians: an outline of the phenomenon

Property Guardians: an outline of the phenomenon

24 April 2018

Author: Jed Meers (lecturer at York Law School)

Many readers may not have encountered property guardianship before. Those that have are likely to have stumbled across a building – perhaps an ex-care home, office block, or council-owned flats – with a sign proclaiming that this ‘property is protected by live-in guardians’. Passers-by may note that many of these premises, such as gyms, working men’s clubs or schools, may not look particularly suitable for habitation, or may wonder on what terms these guardians ‘protect’ them: are they guarding or are they renting?

The basic property guardian proposition is win-win, ie, cheap(er) accommodation for those occupying the property, and a sizeable reduction in the costs of securing otherwise empty premises for the building owner. Research by the authors undertaken for the London Assembly, however, suggests that some problems are widespread.

This short article aims to provide an introduction to the phenomenon, with a focus on three key issues:- extent and geographical reach;

- property standards; and

- the protection of deposits.

Extent and geographical reach

Extent and geographical reachAlthough many of the largest operators in the sector – such as Camelot – have been in operation elsewhere since the 1990s, property guardianship in its current form is fairly recent in the UK, with the bulk of companies being established from 2001 onwards. The exact numbers of property guardians living in the UK is not known. Estimates range from the London Assembly’s figure of 5,000–7,000 guardians across the UK, to Property Guardian UK’s estimate of up to 10,000. It does appear to be the case, however, that the number of property guardians across the UK is growing.

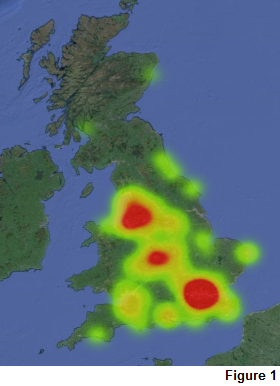

Although much of the high-profile activity in the sector has been confined to London and Bristol, it is important to underscore that the phenomenon is far from restricted to these areas. Our own analysis of property guardian advertisements indicates that companies are operating across England, with clusters of activity not just in London and the South-West, but also in Birmingham, north-west of England and west of Manchester. Figure 1 provides an indication of overall spread using advertisement data mined across 2015.

Property standardsIn our research, the standard of accommodation varied sizably. Guardians were generally reliant on portable electric heaters or oil-filled portable heaters to heat their property, with nearly half having purchased their own form of heating to assist in keeping the property warm. Sixty-two per cent felt able to keep bedroom space comfortably warm over the winter months, though this fell sharply to 45% when asked about other living space within the property. Perhaps connected to these problems, there was a very high prevalence of mould and condensation reported within the sample, with 37% of participants stating it was an issue compared to just 10% in the private rented sector more generally.

In terms of their overall satisfaction with repairs and maintenance, guardians were as dissatisfied as those living in the social rented sector, with 22% expressing disapproval. Of those guardians who were dissatisfied, this was generally because they felt the property guardian company only did the bare minimum with respect to repairs and maintenance, or that they were too slow in getting issues rectified.

DepositsAs guardians are often occupy on licence, the protections afforded to deposits under Housing Act 2004 s212 do not apply. Notwithstanding this, relative to their licence fee payments, property guardians in the sample generally paid as high deposits as those elsewhere in the private rented sector – often outstripping their monthly fee by some margin, with most paying in the region of £700. A significant proportion of respondents highlighted problems with the recovery of deposits at the end of their occupation, with many participants explicitly requesting that deposits be lodged into a deposit protection scheme.

Want more information on property guardianship?For more details on the study, please visit the property guardian page on the London Assembly website.

In an effort to clarify local authority enforcement powers, particularly with regards to the Housing Act 2004, the authors have issued a ‘Pocket Guide to Property Guardians’ which may be of interest to readers, especially those involved in enforcement action. This is available on our project website where you can also sign up to our mailing list.